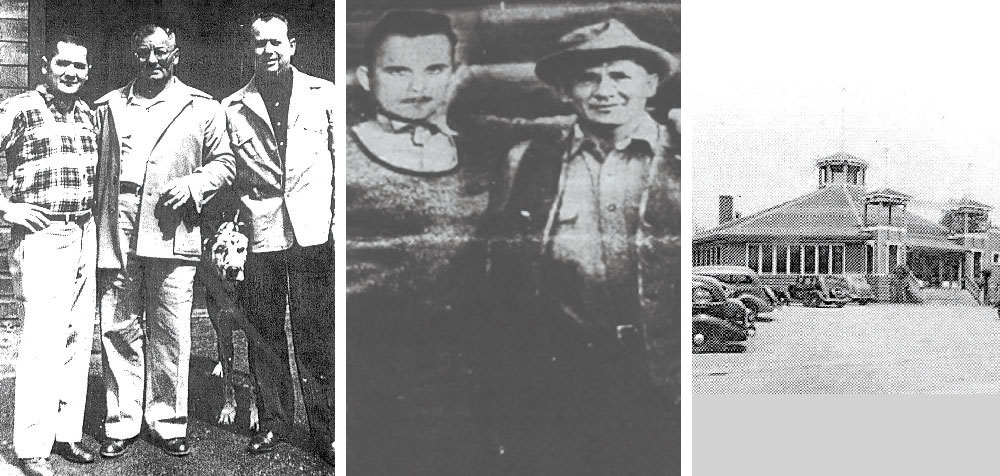

Gangster Highway (Illinois Route 14) runs from Chicago to across the Wisconsin border.

Barreling Down Gangster Highway

Booze, Battles, and Bad Actors

Colonial America’s consumption of alcohol progressed from a standard, oft-daily routine to a chronic national health hazard by the late 1800s. The two-percent, low-alcohol beer served liberally throughout the day (including breakfast) was eventually replaced, in the same quantity and frequency, with distilled grain beverages that carried a significantly

higher alcohol content.

It took time for the culture to realize that the effect of consuming large quantities of grain-based booze was detrimental to one’s health, behavior, and family. There was no police or legal protection for the increasing domestic violence leveled by drunkards. Wives and children were abandoned and left penniless. The jails were full of inebriated bad actors. America had inherited a serious drinking problem.

The anti-alcohol Temperance Movement won its 100-year long battle to ban booze in America. Saloons closed down when Prohibition went into effect on January 17, 1920—making the sale, production, import, and transport of alcohol illegal (though Barrington made the same decision to ban alcohol earlier, in 1908). The new law resulted in a large portion of the American public becoming minor criminals, ignoring the law and partaking of illegal alcohol. This defiant and rebellious culture of the Roaring Twenties was one by-product of Prohibition.

The 1920s: An Era of Fame and Excess

Following World War One, the United States enjoyed a decade of economic growth as it moved into peacetime. The prosperity of the Roaring Twenties invited consumer excess. There was more of everything—and people had the resources to buy it. Mass production introduced affordable lifestyle amenities such as automobiles, radios, and telephones. The wonder of “moving” pictures elevated public entertainment to a whole new level.

Media accelerated American culture through its news with sensationalism and romance as the lead. Notables included Babe Ruth in sports—legendary on and off the baseball field. Aviation heroes Charles Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart drew huge crowds and even larger news coverage. The 1920s movie stars, Greta Garbo, Charlie Chaplin, and Rudolph Valentino gave meaning to the words “matinee idol”. While larger-than-life characters have always existed, the news pushed out the stories of celebrities and heroes with fervor.

Breaking the Bank and the Law

The 1920s was built on a strong economy and Americans were living large. But serious trouble was on the way. The bull market of 1928-29 seemed as if it would last forever—encased in a social, political, artistic, and rebellious cultural bubble. Yet underneath the spirited and jazzed-up Roaring Twenties, the financial infrastructure of the country was about to bottom out. No system existed to mitigate the looming banking fluctuations, nor the oncoming stock market collapse on Wall Street.

October 24, 1929 ushered in America’s most devastating stock market crash. Banks holding worthless stocks in their portfolios became strained, and by 1933, 11,000 of the 25,000 U.S. banks were forced to close. The Great Depression ruined the lives of thousands of individual investors and banks. Confidence in the economy, in banking, and the establishment in general was lost. Disillusion set in. The days of excess withered into America’s Great Depression. Meanwhile, Chicago’s gangster activity rose to an all-time high.

Organized crime was prepared to capitalize on Prohibition opportunity. Mob bosses had earned livings from theft, gambling, and prostitution; but bootlegging and rumrunning made them multi-millionaires. Thirsty Americans also got in on the action, following organized crime underground into hidden speakeasies, until the 18th Amendment that created Prohibition was repealed in 1933.

The Making of Robin Hoods

The 1920s intersection of excess (a time not enjoyed by all), Hollywood and the media fame machines, a public that ignored Prohibition law, and a distrust of banks created a culture that not only tolerated organized crime—but one that hoisted it to a point of mythology. Gangsters with colorful monikers, like “Roger the Terrible” and “Baby Face Nelson” became national “folk heroes” during the heyday of their reign.

News reporters embellished and intensified the stories of gangsters and a disenfranchised, celebrity-hungry public couldn’t get enough. May Jackson, a Deer Park, Illinois resident, was 12 years old in 1934. “Other small-time gangsters would ‘copycat’ the jobs. They all wanted to be like [Al] Capone,” Jackson said.

May Jackson lived in Evanston, and recalled the “excitement and romance—drama that the Europeans [immigrants] had never experienced.” It made the front pages every day, she said, and became the talk of the town. “In the 1920s, newspaper headlines regarding gangland doings were dramatized with special issues, and newsboys on street corners barked, ‘Extra! Extra! Read all about It!’ which sold papers,” Jackson said.

Law-abiding citizens who felt they had been held hostage by events of the Great Depression secretly identified with bank robbers demanding piles of money at the teller window. Well-dressed gangsters morphed into folk heroes—offering drama, excitement, and exaggerated romance, and blurring the line between heroes and villains.

Highway to Hideaways

Chicago was a stronghold for organized criminals that ran bootlegging, prostitution, gambling, and money laundering operations in the early 20th century. By the mid-1920s, the Chicago Outfit had gone viral. Armed with Thompson submachine guns and hefty wallets, gangsters had the means to buy off politicians, police, and judges with threats, bribes, or both.

But like all “businessmen”, the big bosses needed to get away, rest up, and relax. Illinois offered refuge north and northwest of gangster central. It was also a place where mobsters could escape the borders of Cook County law enforcement. Midwestern country roads and forested hideaways were ideal for America’s “most wanted.” They favored Lake Geneva and Northern Wisconsin for refuge, entertainment, and family time. A direct route from downtown Chicago to Lake Geneva was the newly-formed Federal highway, cobbled together in 1933 from a patchwork of Illinois roads designed to connect Chicago to the Winona, Minnesota terminus of an existing Route 14 that went all the way from Winona to Yellowstone National Park.

Heading northwest out of the city became easier in 1933 on the newly formed Route 14 that ran through Barrington and its neighboring towns—and to important gangster destinations. Well-traveled by Public Enemies and the FBI alike—Route 14 emerged as Illinois’ notorious Gangster Highway.

– CHICAGO –

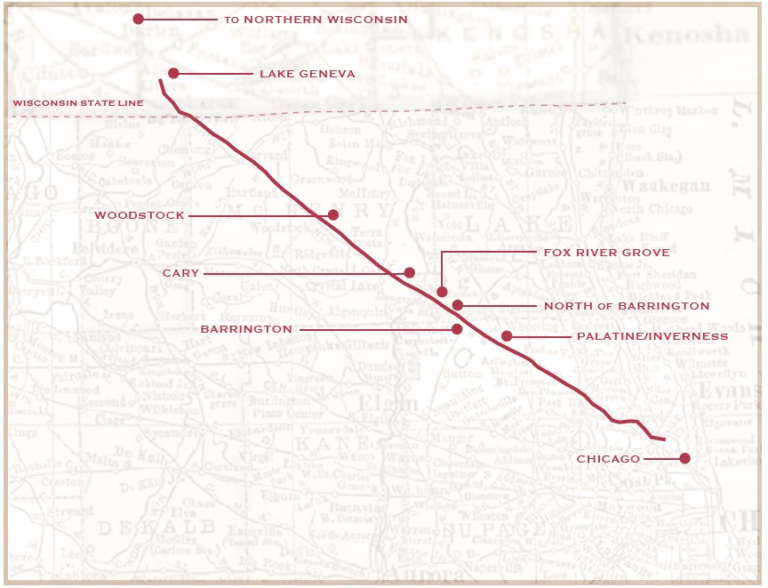

Top, left to right: Alphonse (Al) “Scarface” Capone, Ralph “Bottles” Capone. Bottom, left to right: Frank Capone, Johnny “The Fox” Torrio.

Gangland Headquarters

New York City’s most notorious exports came to Chicago in 1919 to build a criminal empire known as the Chicago Outfit. Johnny Torrio brought his 19-year-old protégé, Al Capone, with him. Six years into the expanding gangster operation, Torrio survived an assassination attempt. But the experience caused him to rethink his job as Chicago’s top crime boss—and he quit and moved to Europe. He handed the reins over to Al Capone.

The Lexington Hotel was a grand, ornate structure designed for glamourous times. It was hurriedly built in 1892 to accommodate the visitors of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The 1890s were boom years for Chicago’s South Side, and the Lexington attracted well-to-do and famous clientele. From 1928 to 1931, Alphonse Capone made the

hotel at 2135 S. Michigan Avenue his gangland headquarters—an association that the hotel’s reputation never escaped. He rented a fifth floor suite of rooms under the name George Phillips. His armed guards kept watch.

Following the good years, the hotel became dilapidated and was never refurbished and reopened. Television news reporter, Geraldo Rivera, staged a live vault break-in at the hotel for a national audience in 1986. Any hope of remaining treasure was dashed when the vault was found empty. Potential new owners surveyed the property in 1980 and found tunnels to taverns and brothels and the usual escape routes for its one-time infamous client.

Al Capone and his brothers, Frank and Ralph, worked together. Ralph was known for his back-room expertise in running the organization, and the mild-mannered Frank lost his life trying to control an election in

Cicero. Al was the public face of the Outfit. He made frequent appearances, “worked” the media, and provided soup kitchens to feed destitute and unemployed Chicagoans. He was the ultimate Robin Hood character.

- PALATINE & INVERNESS -

Fermentation Factory

Bootlegger Roger Touhy realized that Chicago’s water supply wasn’t clean enough for his beer operation. He wanted to brew the best beer possible in Chicago—especially since he sold hundreds of barrels a month to the boss, Al Capone. Touhy found a water supply in Roselle that worked, and he opened up breweries in locations that included the Wilson Farm in what is today known as Inverness. The Wilson Farm, also called “Wolf Stock Farm,” was the perfect place. The farm silos were used for grain storage; the barn held the equipment, and there was a farmhouse next to the barn.

In 1928, Federal agents discovered the operation due to the smell that traveled toward Quentin Road. Back-up support was called in to complete the raid, and the agents destroyed the brewery, which was the largest ever found in Cook County. Capone wanted to take over Touhy’s business. A few years later, Capone’s master plan to have Touhy jailed by framing him worked. But after the jail time ended and Touhy walked free, Capone’s gang killed him a few months later. The farmhouse was moved to its present day location at Route 14 and Quentin. It the 1930s, it was an illegal casino. Today, the building houses Brandt’s restaurant, a local favorite.

– BARRINGTON & NORTH OF BARRINGTON –

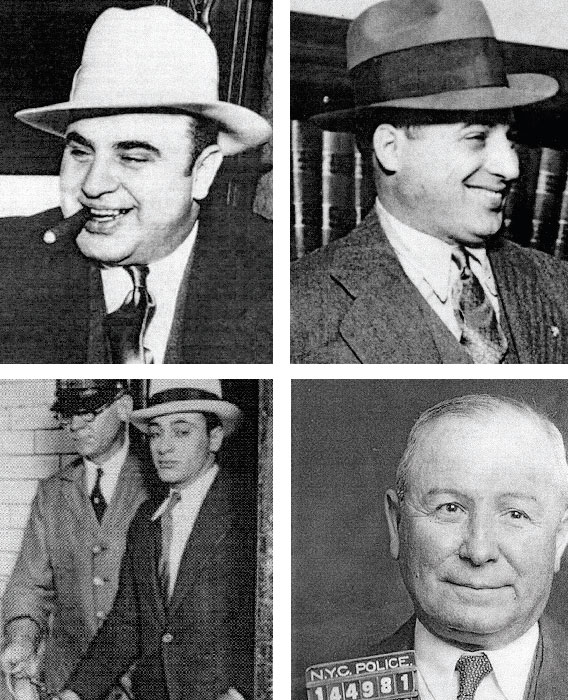

Left: Lester Gillis, also known as “Baby Face Nelson”. Right: A property on Cuba Road is believed to have been part of the Underground Railroad; and later, used by gangsters. The tunnel from the home’s basement ran 300 feet north into the woods. John Dillinger and Baby Face Nelson rented this home. In 1937, Federal agents discovered the tunnel entrance in the basement, cemented it in, and collapsed the exit of the tunnel outside the home. The property was owned by Karen and Jim Tomaszek (above) who operated SafeHouse Farm Alpacas.

The Battle of Barrington

In November 1934, Baby Face Nelson was Public Enemy #1 when he raced through Barrington on Route 14. Nelson and his pals had left Lake Geneva, and were headed toward a farmhouse on Cuba Road that he and John Dillinger rented. But the trip was cut short. Federal agents saw the stolen blue Hudson with the Nelson gang, and pursued a deadly chase. Nelson’s car stopped near the entrance to North Park (now Langendorf Park) and the Feds stopped a short distance ahead. A fierce gun

battle ensued, and two Federal agents died. Nelson was fatally wounded. His body was placed in a car and later dumped at a cemetery in Niles Center by his gang members.

An Ice House Takes a Hit

On Spencer Otis’ estate stood a large, round ice house which fell out of use and over time, collapsed. But in 1931, the body of one of Al Capone’s

victims, Mike DePike Heitler, was found under the rubble when the ice house was set on fire. Mrs. Hattie Gannusch, 60 years old, lived nearby and reported the fire. She called the police and said that three men, whom she believed to be gangsters, were in the vicinity before the fire.

Needle Joints and Backyard Breweries

The Daily Herald reported in June 1926 that in Barrington Center, at Elmer Ranbow’s, 60 barrels of “needle beer” were found behind the barn and other buildings. The brewery operators were adding alcohol via needles into the near-beer barrels to provide the “kick.” The police let air into the barrels to destroy the beverage. Highway police also uncovered a beer plant in Barrington Township. The home of Jim Jurs at Bartlett and Penny Roads had 12 vats of beer undergoing fermentation. There were 20 empty barrels and a truck load ready to go. Jurs was summoned to appear at the police station.

- FOX RIVER GROVE & CARY -

Left photo, from left: Emil Wanatka, Sr., Johnny Meyer (the 1919 U.S. Light Weight Wrestling Champion), and Louis Cernocky at Little Bohemia Lodge. (Fox River Grove Library). Middle photo: John Dillinger with Emil Wanatka, Sr. at Little Bohemia Lodge in 1934. (Little Bohemia Lodge). Left photo: The Crystal Palace (Fox River Grove Library).

The Crystal Palace

There was a destination in Fox River Grove that was friendly to everyone—even gangsters.

Louis Cernocky, Sr., came to Fox River Grove in 1919 with his wife, Mary, and son Louis, Jr. They invested in the town and opened up a small café on Route 14 at Lincoln Avenue. A second roadside stop, Louis’ Place, replaced the first one, which was torn down. Louis’ Place then morphed into a two-story brick building. Nearby, Cernocky added an eight-sided Crystal Palace, which opened up big band sounds for the area. It also opened its doors to Ma Barker and John Dillinger’s gang. Cernocky was also associated with Al Capone during Prohibition. Old-

timers from Cary and Fox River Grove told tales of digging the get-away and storage tunnels there.

Louis, Emil, John, and Louis

Louis Cernocky was friends with Emil Wanatka, Sr., who headed north in 1929. Wanatka bought land and built a retreat in Manitowish Waters, naming it Little

Bohemia Lodge. Emil Wanatka and John Dillinger shared the same mob attorney, Louis Piquette, an indirect connection. During the early 1930s, Cernocky’s Fox River Grove establishment was a refuge for Dillinger and his gang, including Baby Face Nelson. It was a trusted rendezvous place. Dillinger bunked overnight when needed. He held a large meeting of his crew there in April 1934. When Dillinger and Nelson needed to lay low, Cernocky recommended the trip to Little Bohemia Lodge in 1934. He handed Dillinger a sealed note of introduction for Emil Wanatka, and then the gang left town in four cars to take the 365-mile trip to Northern Wisconsin.

Cary’s Fortress on a Hill

John D. Hertz was owner of the Yellow Car Company and also founded the Hertz Rental Car Company. Chicago’s gangsters ran the unions during the first half of the 20th century—but that didn’t stop Hertz from hiring non-union cab drivers. Having made enemies there, including a taxi competitor who turned to violence, Hertz needed a refuge away from the city. Across the Fox River, a few miles from Louis Cernocky’s Crystal Palace, Hertz bought a 900-acre riverside parcel, naming it Leona Farms. When Hertz was in town, state police would guard the front gate. There were gun turrets in the third level of the horse barn’s loft and 100 employees to keep watch. Hertz and his wife, Fannie, held Gatsby-style parties, and owned thoroughbreds, including Reigh Count, winner of the 1928 Kentucky Derby. (Shirley Beene)

- WOODSTOCK & LAKE GENEVA -

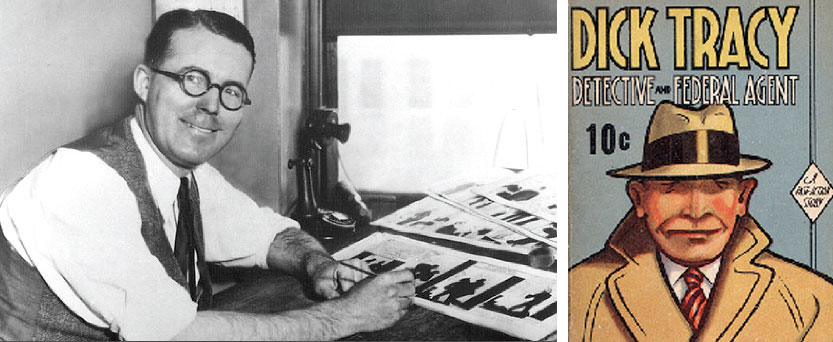

Chester Gould at the Chicago Tribune. Right: A 1936 Dick Tracy book. (Used by Permission,©2015 Tribune Content Agency)

Woodstock’s Cartoon Crimestopper

On October 4, 1931, a local crime-fighting hero was born. The Oklahoma-born creator of “Dick Tracy” lived out his dream by creating an iconic cartoon character for a major newspaper—the Chicago Tribune. Gould lived in the Bull Valley area of Woodstock, just a few miles off Route 14.

The character Dick Tracy was successful where the FBI was not. “I decided that if the police couldn’t catch the gangsters, I’d create a fellow who could,” Gould said.

Dick Tracy was a creation of the Prohibition era, with its warfare, weapons, and gangsters. Tracy pursued lawless characters who were given code names like “Pruneface,” “Flattop,” “Larceny Lou,” and even a love interest, “Tess Trueheart,” whom Tracy married in the comic strip. The stories and candy cards were at times surprisingly violent, and also included women and children in the vignettes.

The last Dick Tracy cartoon book was issued as No. 5 in May 1991. In that issue, Gravel Gertie and the tobacco-spitting B.O. Plenty were finally married.

Lake Geneva – Clubs and Getaways

Route 14 led the good guys and the bad guys north to Lake Geneva, where relaxation was the order of the day. George “Bugs” Moran, a rival of Al Capone, was so fond of the Lake Como Inn on Lake Como that a suite was named after him. The inn had a gambling room with slot machines, and a speakeasy in the basement to entertain guests—a gangster’s paradise. Baby Face Nelson also visited the area and the Lake Como Inn. The gangster’s wives and molls shopped on the streets of downtown Lake Geneva. It was a time to get away from the all the racket.

- NORTHERN WISCONSIN -

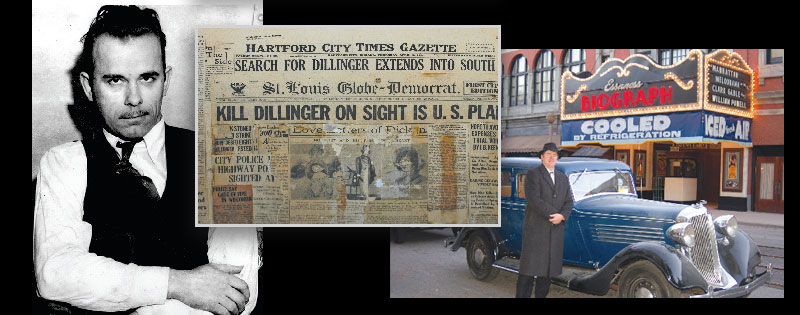

Left: John Dillinger. Even his tie was crooked. Right: Barrington resident Jeff Kelch owns this sedan that was used in the 2009 movie, Public Enemies starring Johnny Depp. A scene using Kelch’s car was filmed at the Biograph Theater in Chicago where Dillinger was fatally wounded by the FBI.

The Last Resort

It was just friends helping each other. Or was it? Louis Cernocky in Fox River Grove felt that his friend Emil Wanatka could be trusted. The two knew each other, and attorney Louis Piquette—also Dillinger’s council. Cernocky recommended to John Dillinger, Baby Face Nelson, and the rest of the gang that they head to Northern Wisconsin to lay low. Cernocky handed a note for Dillinger to deliver to Little Bohemia Lodge owner, Emil Wanatka, to make the introduction. The stated sum of $500 for the rented rooms would help Wanatka during his slow season in April 1934. But Dillinger was worth far more to the Feds—a cool $10,000.

The gang arrived, had a meal and a few drinks, and took to playing cards. Wanatka saw Dillinger’s gun beneath his coat and became concerned. He checked some newspapers and figured out who his guests really were. An elaborate plan was made whereby Wanatka’s wife would go to town to call the police. A team of Chicago FBI agents flew up to Rhinelander in response the next day.

When the Feds approached the Little Bohemia property on that snowy night, a car full of three men was leaving the lodge. The FBI called for a halt—but the two Civilian Conservation workers and a salesman did not hear the command. The FBI killed one, injured another, and the third man ran.

Those gunshots on April 23, 1934 alerted the Dillinger gang, who grabbed their things and made an escape along the shore of Little Star Lake by the lodge. Wanatka and three women ran to the basement. The FBI let loose on the lodge, tearing it apart with gunfire. But it was too late. The boys were gone.

The End of an Era

Five years earlier than the Little Bohemia disaster, the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre in Chicago began to dampen the public’s infatuation with gangsters. On July 22, 1934, Dillinger was killed by FBI in Chicago. He was 31. In September 1934, Louis Cernocky died of a heart attack at age 49. Baby Face Nelson was 26 when fatally wounded in Barrington in 1934. His young, troubled life ended on Gangster Highway.

– End –

Share this Story