Lake County’s Dunn Museum | Margaret McSweeney’s Midlife Culinary Adventure

Designing Barrington Lifestyles

Lake County’s Dunn Museum

Visitors Arrive Curious, and Leave Inspired

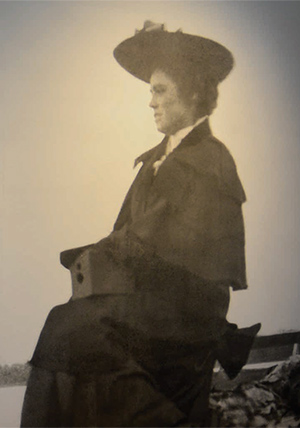

Bess Bower Dunn (1877– 1959) made history in lasting ways, including with her photography, film acting, and local government service. Here she is seen holding what appears an antique Eastman Kodak No. 2 Bullseye box camera, c. 1906.

How many Barrington area residents today remember that on Quentin Road between Long Grove and Lake Cook Roads there was a Nike Missile site, one of a defensive ring of such sites around Chicago, constructed during the Cold War? And how many people remember or knew that once the site was decommissioned, it became the temporary home for the collections of Lake County history?

For approximately a decade from 1965 to 1975, some 20 feet underground, priceless artifacts and memorabilia that formed the lifelong collecting passion of Bess Bower Dunn—and which had been acquired by the Lake County Forest District as the nucleus for a county museum—were carefully stored. These artifacts awaited the day they would see the light again, to provide a sense of place, to inform, and to preserve the history of a county in which the archaeology and paleontology provides evidence of human occupation going back thousands of years.

A Pioneering Woman

But who was Bess Bower Dunn, the remarkable, and much-loved woman, who did have a sense of place and made it her life’s avocation to record and photograph the stories of those, who like her own family, had come west in pioneer days, to settle in the lakeside town first called Little Fort, then in 1849, changing its name to Waukegan, the Pottawatomie equivalent of “Little Fort”. Her parents were Susan and John Bower from Pleasant Valley, Dutchess County, New York, who, by 1873 had moved to Waukegan. Bess, born in 1877, was their second daughter.

Left: The newly re-branded Dunn Museum is located in Libertyville. Right: A replica dryptosaurus greets Dunn Museum visitors.

The beginning of her interesting life came in 1898, when she and a friend, Isabelle Spoor, appeared as lady boxers in a film made by pioneer movie maker Edward Amet, and they were said to be the first women in a film. In 1899, Bess became a Lake County employee in the county treasurer’s office. She moved to the county clerk’s office and in 1922 transferred to the probate clerk’s office, where she was chief deputy clerk when she died in September 1959. She had become known as “Miss Information”, reflecting her life-long collecting of Lake County’s history in notes, photographs, and many historical objects and antiques, which crowded the house at 212 Julian Street in Waukegan, the family home where she lived for 71 years until her death.

James Getz, then president of the Lake County Historical Society, said at her death, that she had done more than any other individual to preserve Lake County history. As Arnett C. Lines is to Barrington, so Bess Bower Dunn is to Lake County.

In 1918, she had married Roland Ray Dunn, the son of Byron A. Dunn, who from 1904 to 1908 operated the Waukegan Gazette, the first daily paper ever published in the county. Dunn died in 1928.

Tool chest and tools of William Bonner (1815-1881) are showcased in a farm exhibit.

Her collections formed the nucleus for a private Lake County Historical Society in 1959 in Wadsworth, and the collections were transferred to the Nike Missile site in 1965. After the 10 years underground at Quentin Road, the light of day came. The Lake County Forest Preserve District acquired Lakewood Farms, with its country residence and complex of farm buildings that were created in 1937 by Chicago contractor Malcolm Boyle. When Boyle sold the property, it was one of the largest farms in Lake County. The house was gradually adapted for museum exhibits and other areas to provide climate-controlled storage facilities for collections that would eventually number some 20,000 artifacts and 1,000 linear feet of archival materials.

Here, what became the Lake County Discovery Museum, stayed for 40 years, until it was realized that the buildings were no longer adequate for the permanent preservation of the collections, and to provide exhibition space large enough to tell the history of the county in a meaningful way, offer a classroom directed towards residents of all ages for educational programs, and have study rooms for those interested in genealogy and archival study.

When the museum was closed in fall 2016, an intensive period of planning began for what the Lake County Board had decided could provide an appropriate location to re-envision the museum and bring it to the standard where it would be accredited by the American Alliance of Museums, a distinction only carried by five percent of museums.

A New Identity

The Lake County Forest Preserve District headquarters at 1899 West Winchester Road in Libertyville offered a first floor that doubled the previously available exhibition space at Lakewood, and a lower level that could be adapted for climate-controlled storage of artifacts and archives. But as Andrew Osborne, superintendent of educational facilities for the Lake County Forest Preserves recalled, it was realized that the museum also needed a new identity. After all, there are innumerable Lake Counties in the United States. As the staff looked at the origins of the collections and learned more about the woman who had spent a lifetime gathering the history, it became clear that there was no greater tribute than to name the re-envisioned museum for her.

Barbara L. Benson, Barrington's Historian and journalist, with Andrew Osborne, superintendent of educational facitlities for the Lake County Forest Preserves.

First, an online survey was conducted concerning renaming the museum, and then ensuring that there were no close living relatives of Bess who might object to the use of her name (see sidebar) and then the work began that would transform what had been offices, into a lively and informative walk through thousands of years of Lake County history. Original artifacts enclosed in display cases are given interactive life through reproductions of infinite detail. The narrative now both informs and engrosses all ages of visitors. But first, you must greet the gatekeeper, DRYPTOSAURUS! Imagine this toothy character, a biped with eagle-like talons roaming through the wide, open plains that were the world of these monumental characters over 67 million years ago, long before the Ice Age. It took a year for paleo-artist Tyler Keillor to create Dryptosaurus, which is believed to have been only half the size of Tyrannosaurus Rex. This Dryptosaurus is the only one known of its kind in any museum.

An Amazing Backyard

Andrew Osborne is especially proud of the fact that, while exhibits were professionally designed, they were all built in-house. Lake County’s story is told with clarity, ease, and accuracy, and a visitor will indeed leave inspired.

The Bess Bower Dunn Museum has one unique aspect, it is owned by the Lake County Forest Preserve District which has over 31,000 acres in its holdings. A feature of the exhibits is referring visitors to historical sites that can be visited in those forest preserves. It is history at its most compelling, as the indoor museum has a 31,000-acre backyard.

The forest preserve acquisitions were in their beginnings when Bess Bower Dunn died. She was as concerned about the environment as she was about an old settler’s table or chair. Today, she would surely be amazed and inspired at what Lake County has achieved for environmental and history preservation. How appropriate that the re-opened and re-envisioned museum should be named for her. After all, she had provided the nucleus for its original collections. Aren’t you curious?

To learn more about the Bess Bower Dunn Museum of Lake County, visit www.lcfpd.org/museum.

- - - - - - - - -

A Family Connection

By Barbara Benson

When it was first announced that Lake County was considering naming their museum for Bess Bower Dunn, and were seeking contact with any relatives of Bess, I knew that my husband’s family had a story and memorabilia to offer them.

My late husband, Laurence Benson, and his late sister, Barbara Benson Leech of Deerfield, came from a family, the Merchants, who were among the first residents in Waukegan in the 1840s. My husband and his sister grew up in the original family home at 220 Julian Street, four houses removed from Bess Bower Dunn at 212 Julian Street. The Merchant and Bower families knew each other well.

Margaret Merchant first married Harry Benson, the father of my husband and his sister. Later in life she married Dennett Grover, son of Edith Bower Grover and therefore a nephew of Bess Bower Dunn. His mother Edith, was the elder sister of Bess, born in 1875. Edith married Alonzo Grover, and they moved two years later first to the State of Washington and finally settling in Portland, Oregon, where it is believed the Grovers were from. They had three children, John, Octavia, and Dennett.

“Uncle Denny” as he was known to the younger members of the family, was, as I am remembering now, always in love with my late mother-in-law, who was a very dynamic and attractive woman. Their marriage was the third for her and the first for him sometime in the 1950s. He returned many times in his adult life to Waukegan, and after he and Margaret married, they lived at 220 Julian Street.

He must have had something of his Aunt’s collecting inclinations. He was always bringing some new and interesting object or piece of furniture home. One of his favorite haunts was the Salvation Army store in Waukegan.

Margaret Merchant Grover died in 1980, the fourth and last generation of the Merchant family to live at 220, as we always called it. After her death, Denny returned to live with his sister in Portland.

I shared this story with Katherine Hamilton Smith, and Diana Dretske at the Lake County Museum, and members of our family were invited to attend the Preview Opening for the Bess Bower Dunn Museum of Lake County on March 23, 2018.

I think that we were the only ones with any familial link to Bess. We regretted only that my husband and his sister were not there to share their memories of Bess from their childhood at 220 Julian Street, that house now 175 years old.