Making Dreams Come True | Welcome Home - Moretti’s Barrington

Remembering Bobbie

A Tower Lakes family recalls their grandmother who survived Chicago’s titanic-sized disaster in 1915 on the ill-fated SS Eastland that claimed 844 lives.

Borghild “Bobbie” Aanstad as a young teen on an unknown beach.

They called her “Bobbie”.

Borghild Amelia “Bobbie” Aanstad was just four days shy of her 14th birthday that morning in Chicago when the Norwegian-immigrant-turned-American-teen strode confidently up the gangplank to a massive excursion steamer.

She simultaneously walked into history.

The most salient fact about Bobbie was that she did not die that day and did not join the 844 other partiers who drowned in the Chicago River. The deadly morning of July 24, 1915 dawned gray and misty.

Death reached out for her inside the hulk of the massive SS Eastland on the deadliest day in Chicago history, but could not grab her. Luck? Maybe. Fate? Possibly.

The Eastland shown on Lake Michigan while owned by the St. Joseph-Chicago Steamship Company, months before the tragedy.

Bobbie’s mother, little sister, AND UNCLE also survived, though they did not know Bobbie’s fate for many hours.

The ship—a top-heavy, unstable behemoth nearly the length of a football field and four-plus stories tall—leaned right, then left, and began to list irretrievably as it prepared to get underway.

On July 24, 1915, at 7:30 a.m., the dockside-tied Eastland barrel-rolled left like a dying whale, launching topside passengers into the river and trapping hundreds below decks. It was a young crowd of revelers, mostly blue-collar immigrant families, encouraged by the host, Western Electric’s massive telephone-making operation in Hawthorne—a working-class Chicago suburb that became Cicero—to join the trip to Michigan City, Indiana, for a day of music, games, and food.

The 844 all died within 30 minutes. Seventeen hundred survived. Police lining the pier said the shrieks of terrified children screaming would haunt them for years.

But Bobbie had an edge. She was athletic, sturdy and lithe, but mostly she knew how to swim. Teen-aged beau Ernie Carlson had taught her to swim on a joint family vacation in Michigan.

So, she paddled and treaded water inside the nearly submerged cabin for hours until help came. Corpses bobbed around her.

“Bobbie” had saved herself and became a family’s inspiration.

Life and death were random and brutal companions that day. Two little neighborhood girls sat side-by-side on a bench holding hands. They were best friends. One lived; the other died. There were heroes who leaped from the pier to save anyone they could reach. There were villains, who stole valuables off the bodies of drowned passengers.

And, then, as if it had never happened, Chicago forgot the capsized Eastland and its drowned souls as if they had never existed. But it was worse than misplacing memory. Chicago ignored the Eastland heartache.

Passengers hang on to the side of the turned ship.

A Family’s Masterwork

That ended in 1998 when Bobbie’s surviving heirs could stand the long, bleak silence no longer. Co-founders Susan Decker and Barbara Decker Wachholz, Bobbie’s only grandchildren, joined Barb’s spouse, Ted Wachholz, in forming the Eastland Disaster Historical Society. He had never heard of the Eastland until he met Barb when he was 25.

The Society became their family affirmation of “Nana,” as they all called her. And just as intently, they desired to empty Chicago’s most tragic day of its quiet desolation. So many people didn’t know. Families suffered ancient loss without release or accountability.

The family trio sat down in the Wachholzes’ lakeside home in Tower Lakes north of Barrington recently to assess the history they found. And why.

They started from zero and created a permanent institutional legacy, a gift to families. “This was always about the people,” Ted said.

“It was clear to us that if Nana had died that day, we would not exist,” Barb added. “We would not have had our children.”

The event wiped out generations. Twenty-two entire families—parents, children, aunts, uncles, cousins—died. Often in each other’s arms. They were laid out, nearly all of the 844, in a city armory converted to a morgue, waiting for someone to identify them.

The Society has reached a singular plateau this year. Each new fact, as Ted notes, becomes another brush stroke in the painting.

This is the family’s masterwork, a testament to remembering. The massive, carefully accumulated original documents, photos, court records, police and firefighter accounts, as well as eyewitness accounts have been turned over to the prestigious Newberry Library of Chicago for permanent archiving and digitalization.

Family records of everyone aboard the ship have been donated to the Chicago Genealogical Society. Artifacts donated by surviving kin—including a husband’s and wife’s wedding rings—are housed in local museums. None of those now-permanent exhibits would exist as is without the Society.

“What remains to be found,” Ted Wachholz notes, “are the records of many thousands. Maybe it’s as many as millions of descendants. We have connections to families now in 47 states and some in Europe. The new connections show no signs of slowing down.”

The inspiration to this decades-long effort was a child, wife to Leonard Decker, Sr. in 1922, then mother, and grandmother, and great-grandmother who was revered. She never let that day taunt her. She was forever a blithe spirit whose arrivals for family visits were never-quiet celebrations.

“She was effervescent,” Susan Decker said. “She never lost her love for the water and swimming. She taught her son to swim and made sure we all knew how to swim. But mostly she was the kind of grandmother that everyone wishes had been theirs. She was fun.”

She never turned her back on delightful joy, or let the Eastland determine who she would be.

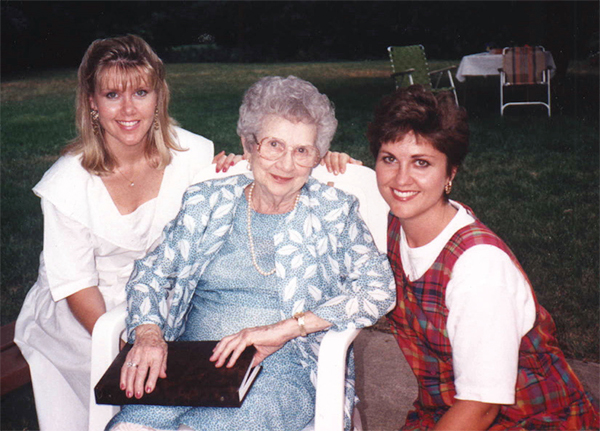

Borghild “Bobbie” Aanstad Carlson on her 90th birthday (July 28, 1991), with her only grandchildren, Susan Decker (left) and Barbara Decker Wachholz (right). She passed away peacefully five days later.

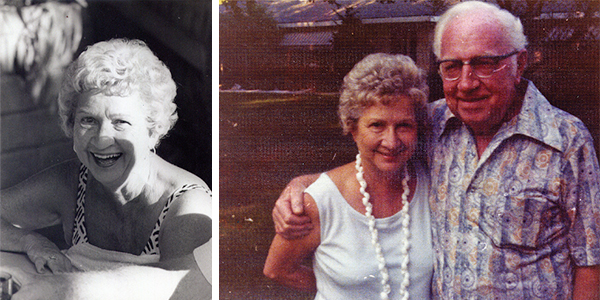

Borghild “Bobbie” Aanstad Decker Carlson while married to Ernie Carlson and living in California.

An Extraordinary Reunion

Then, when she was a widowed 75-year-old, a letter came. It was from Ernie Carlson in California. They had not seen each other or talked for 60 years. He, too, was widowed and wanted to know if they could meet. They did, in Chicago. And they fell in love all over again. They wed and began what “Bobbie” could call “the best (seven) years of her life,” before Ernie passed away in 1983.

On her last day, she was 90. She slept contentedly. As midnight passed, so did her last breath. She never awoke.

The Eastland tried to kill her. But it failed. “Bobbie” would plot her own course that morning, and all the mornings that followed.

- - - - - - -

The Eastland Disaster Historical Society is celebrating its 21st year as a resource for the families of victims and survivors. Ted Wach- holz is the executive director and can be reached at 844-724-1915. Written correspondence can be mailed to P.O. Box 2013, Arlington Heights, IL 60006. Visit EastlandDisaster.org.

- - - - - - - - -

David Rutter’s career spans 45 years as publisher, editor, writer and columnist at seven daily newspapers in five states. He wrote columns for the Chicago Tribune’s suburban newspapers and won Chicago’s Lisagor Award for editorial writing. He has written three books, and teaches personal memoir writing at the region’s community centers and libraries. Rutter lives in Lake Villa. He can be reached at david.rutter@live.com or 847-445-7684.