Chicken Pot Pie and Cut-Rate Whiskey | Designing Barrington Lifestyles

Barrington Horse Country

Chicken Pot Pie and Cut-Rate Whiskey

Some Staples of Life in Early Barrington

Eating out was not an option in a country outpost, but was perhaps not necessary. Wild game was plentiful on the prairie; hunting and trapping were part of everyday life. The clear waters of the many small lakes and streams teemed with fish. Many settlers and later residents kept livestock and raised their own produce. In early village days, a chorus of roosters substituted for alarm clocks. Wild fruits were plentiful and a corn patch graced almost every back yard. Staples such as flour and sugar and coffee were purchased at one of the general stores, but their ads focused more on dry goods than provisions, as seen in the pages of the early Barrington Review newspaper. Another source of fresh vittels were the dairy farms that grew up around Barrington. While most of their milk production was shipped to the city from the platforms in Barrington or Cuba Station at Kelsey and Plum Tree Roads, their cheese factories provided the locals with processed wheels of new and aged cheeses.

A circa 1872 Advertising Circular, or “Dodger” as it was then called, was put out by a citizens committee and stated the following: “The adjacent dairy farms have long been noted for an excellent quality of milk furnished to the Chicago Market, commanding frequently a higher price than any other. A competent man supplies the citizens of Barrington. There are several CHEESE FACTORIES within six miles, manufacturing a superior article of this kind of food.”

So there was an abundance of fresh foods which were surely very flavorful. Preservatives took the form of brining and smoking. But what of the cooking? Until the early 20th century, the continuously burning wood fires and wood stoves with their cast iron stockpots and bread and muffin trays were ever ready for the next meal to be prepared, and of course, a supply of hot water for washing and the weekly bath. Would we have enjoyed the food? It would have been flavorful and wholesome, and an understanding of how close was earth to table explains the renewed demand for organic foods today, and the popularity of farmer’s markets in recent years.

For an account of a Christmas meal in a typical Barrington household of the late 19th century, there is no better description than that provided by Emaline Hawley Brown of the Octagon House in one of her letters to her daughter Laura in Minnesota. For Christmas Day, 1897, their meal included roast duck, mashed potatoes, bread and butter, doughnuts, sweet crackers, and angel cake, peach sauce and apples “as large as your fists, not a very elaborate dinner but we all enjoyed it.” All cooked on their wood burning stove.

A few years later there was an elegant soiree at the Robertson House on West Main Street. Built in 1898 on a grand scale with a ballroom on the third floor, entertaining was certainly in the minds of John and Julia Robertson. One event of March 6, 1905 was noteworthy in that it received a most enthusiastic report by Mrs. Mae Lane Spunner in the Barrington Review. The occasion was a dinner in honor of the Women’s Thursday Club of Barrington and after praising the exquisite floral arrangements and the beautiful costumes of the ladies, Mrs. Spunner writes:

“Promptly at eight o’clock all were summoned to partake of an elaborately arranged and prepared chicken pie dinner and covers were laid for fifty. For an hour and a half guests lingered around the festal board, and that the gentlemen thoroughly enjoyed and appreciated the efforts of the ladies was evidenced by the hearty manner in which each responded to a toast to the club when the repast was ended.”

Mrs. Robertson was known to have servants, and the chicken pies for 50 people were cooked in wood burning ovens, because ironically gas mains were only introduced into the Village of Barrington in June of 1905. It is too bad that we don’t know the rest of the menu.

Emaline Hawley Brown and her daughter Hattie very often had references to the impact of liquor on Village life in their letters to Laura Brown Nightingale in Minnesota. For instance, in 1889, the E.J.& E (now CN) Railroad was being constructed through Barrington. Hattie wrote to her sister on September 4th: “The railroad men are so thick on the streets nights and so full and so mean, I dare not go anywhere alone. Last night they had a keg of beer in front of Crabtree’s house (west of the Octagon House on West Main Street), and had a war dance around it, that was about seven o’clock.”

On October 3 she wrote: “The railroaders go to Spalding every noon for water and for more rails and ties, and they stay there nights. The boss says he don’t want the men to stay here nights for they will get so drunk they will not work.”

In 1893, the first of several major fires in the downtown area was bringing about new building, and the relocation of businesses. One notable opening was that of George Foreman’s saloon in the building where Anderson’s Chocolate Shop is now. While recording all of the details for Laura in Minnesota, Emaline notes in a March 1893 letter: “We have five saloons in town, each has to pay five hundred dollars license, so we ought to have good roads.”

The first well-documented restaurant was “Mother’s Place”, a restaurant on the north side of East Main Street. It was operated by “Nanny” Atkins as everyone in Barrington called her. She was the mother of George Atkins who owned the next door Dayton Hotel. The family had originated from Dayton, Ohio. Now and then, “Nanny” would hand out cookies to local children. This was in the early 1900s, and recalled by Marvin Snyder, a prolific chronicler of those years in Barrington.

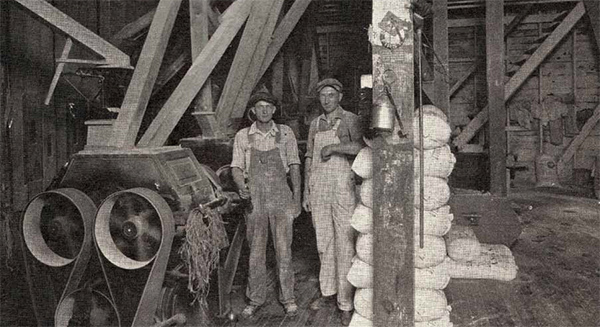

During Prohibition years from 1920 to 1933, there was much nefarious and “spirited” activity in the Barrington countryside. The associates of Al Capone had their contacts in the outlying farms and largely unregulated county lands. The late Bill Klingenberg, another well-loved chronicler of the area, taking visitors and historians on sightseeing drives, would point out with great alacrity where an illegal still had been located, or as he referred to them, “blind pigs”. Local residents would be in-the-know on these resources, but few are left to tell the tales of those “nod and a wink” days when under-the-counter cash was a necessity if one wanted liquid refreshment for the spirit, stronger than tea, coffee, or lemonade.

Perhaps the most famous eatery in Barrington’s mid-20th century past was Bert’s Bank Tavern. Opened in 1933 by Jack Welch as The Last State Bank Tavern in the building on the corner of Cook Street and Park Avenue, where the First State Bank of Barrington had failed the year before, the restaurant featured the teller’s cages and the vault area as “booths”. Welch was joined by Bert Peterson, who later bought him out, and “Bert’s Bank Tavern” became one for the history books. The succulent burgers, cooked on an open grill, and the homemade pies baked by Ed and Leo Brommelkamp’s wives were renowned, even drawing diners from Chicago.

For earlier generations of Barrington residents, it was one of the favorite gathering places in town. When Bert’s closed in 1969, it was the end of an era. Or was it? Since then, there have been several successful and well-known restaurants in historic buildings. But that is another story.

Certain it is that early Barrington residents were well-fed and refreshed from mostly local resources, whether it was Magullion stew, chicken pot pie, or cut-rate whiskey over and under the counter.